Art and Imagery Depicting the Prophet Muhammad Were for the Purpose of

The permissibility of depictions of Muhammad in Islam has been a contentious outcome. Oral and written descriptions of Muhammad are readily accepted by all traditions of Islam, but in that location is disagreement well-nigh visual depictions.[1] [2] The Quran does not explicitly or implicitly forbid images of Muhammad. The ahadith (supplemental teachings) present an ambiguous picture,[3] [4] but at that place are a few that have explicitly prohibited Muslims from creating visual depictions of man figures.[5] It is agreed on all sides that there is no authentic visual tradition (pictures created during Muhammad's lifetime) as to the appearance of Muhammad, although there are early legends of portraits of him, and written concrete descriptions whose actuality is often accepted.

The question of whether images in Islamic art, including those depicting Muhammad, can be considered as religious art remains a matter of contention amidst scholars.[half-dozen] They appear in illustrated books that are normally works of history or poetry, including those with religious subjects; the Quran is never illustrated: "context and intent are essential to understanding Islamic pictorial art. The Muslim artists creating images of Muhammad, and the public who beheld them, understood that the images were not objects of worship. Nor were the objects so decorated used as part of religious worship".[7]

However, scholars concede that such images have "a spiritual element", and were also sometimes used in breezy religious devotions celebrating the mean solar day of the Mi'raj.[viii] Many visual depictions only bear witness Muhammad with his face up veiled, or symbolically represent him as a flame; other images, notably from before about 1500, show his face up.[nine] [10] [11] With the notable exception of modern-twenty-four hours Islamic republic of iran,[12] depictions of Muhammad were rare, never numerous in any community or era throughout Islamic history,[13] [fourteen] and appeared about exclusively in the private medium of Western farsi and other miniature book illustration.[15] [16] The fundamental medium of public religious art in Islam was and is calligraphy.[fourteen] [15] In Ottoman Turkey the hilya developed as a decorated visual arrangement of texts about Muhammad that was displayed as a portrait might be.

Visual images of Muhammad in the not-Islamic Westward accept always been exceptional. In the Middle Ages they were mostly hostile, and almost oftentimes appear in illustrations of Dante's poetry. In the Renaissance and Early Modern period, Muhammad was sometimes depicted, typically in a more neutral or heroic lite; the depictions began to encounter protests from Muslims. In the age of the Internet, a scattering of caricature depictions printed in the European press accept caused global protests and controversy and been associated with violence.

Background

In Islam, although nothing in the Quran explicitly bans images, some supplemental hadith explicitly ban the drawing of images of any living creature; other hadith tolerate images, merely never encourage them. Hence, nigh Muslims avoid visual depictions of Muhammad or any other prophet such equally Moses or Abraham.[1] [17] [18]

Most Sunni Muslims believe that visual depictions of all the prophets of Islam should be prohibited and are especially averse to visual representations of Muhammad.[20] The key concern is that the use of images can encourage idolatry.[21] In Shia Islam, however, images of Muhammad are quite mutual nowadays, fifty-fifty though Shia scholars historically were against such depictions.[twenty] [22] Still, many Muslims who take a stricter view of the supplemental traditions will sometimes challenge any depiction of Muhammad, including those created and published by not-Muslims.[23]

Many major religions have experienced times during their history when images of their religious figures were forbidden. In Judaism, one of the Ten Commandments states "Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image", while in the Christian New Testament all covetousness (greed) is divers as idolatry. In Byzantine Christianity during the periods of Iconoclasm in the 8th century, and again during the 9th century, visual representations of sacred figures were forbidden, and only the Cross could exist depicted in churches. The visual representation of Jesus and other religious figures remains a concern in parts of stricter Protestant Christianity.[24]

Portraiture of Muhammad in Islamic literature

A number of hadith and other writings of the early Islamic period include stories in which portraits of Muhammad appear. Abu Hanifa Dinawari, Ibn al-Faqih, Ibn Wahshiyya and Abu Nu`aym tell versions of a story in which the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius is visited past two Meccans. He shows them a cabinet, handed down to him from Alexander the Great and originally created by God for Adam, each of whose drawers contains a portrait of a prophet. They are astonished to run into a portrait of Muhammad in the final drawer. Sadid al-Din al-Kazaruni tells a similar story in which the Meccans are visiting the male monarch of China. Kisa'i tells that God did indeed give portraits of the prophets to Adam.[25]

Ibn Wahshiyya and Abu Nu'ayn tell a second story in which a Meccan merchant visiting Syria is invited to a Christian monastery where a number of sculptures and paintings describe prophets and saints. There he sees the images of Muhammad and Abu Bakr, as yet unidentified past the Christians.[26] In an 11th-century story, Muhammad is said and then take sat for a portrait by an artist retained past Sassanid male monarch Kavadh II. The rex liked the portrait then much that he placed it on his pillow.[25]

After, Al-Maqrizi tells a story in which Muqawqis, ruler of Arab republic of egypt, meets with Muhammad'south envoy. He asks the envoy to describe Muhammad and checks the clarification against a portrait of an unknown prophet which he has on a piece of cloth. The description matches the portrait.[25]

In a 17th-century Chinese story, the rex of Mainland china asks to see Muhammad, but Muhammad instead sends his portrait. The king is so enamoured of the portrait that he is converted to Islam, at which indicate the portrait, having done its task, disappears.[27]

Depiction by Muslims

Exact descriptions

In one of the primeval sources, Ibn Sa'd'due south Kitab al-Tabaqat al-Kabir, there are numerous verbal descriptions of Muhammad. One description sourced to Ali ibn Abi Talib is as follows:

- The Apostle of Allah, may Allah anoint him, is neither besides short nor too alpine. His hair are neither curly nor straight, simply a mixture of the two. He is a man of black pilus and big skull. His complexion has a tinge of redness. His shoulder bones are broad and his palms and feet are fleshy. He has long al-masrubah which ways hair growing from neck to navel. He is of long center-lashes, shut eyebrows, smooth and shining fore-head and long space betwixt ii shoulders. When he walks he walks inclining as if coming down from a summit. [...] I never saw a man like him earlier him or after him. [28] [ unreliable source? ]

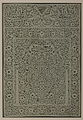

From the Ottoman menstruum onwards such texts accept been presented on calligraphic hilya panels (Turkish: hilye, pl. hilyeler), ordinarily surrounded by an elaborate frame of illuminated decoration and either included in books or, more often, muraqqas or albums, or sometimes placed in wooden frames and so that they can hang on a wall.[29] The elaborated form of the calligraphic tradition was founded in the 17th century by the Ottoman calligrapher Hâfiz Osman. While containing a concrete and artistically appealing description of Muhammad'south appearance, they complied with the strictures against figurative depictions of Muhammad, leaving his advent to the viewer'southward imagination. Several parts of the complex design were named subsequently parts of the torso, from the caput downwardly, indicating the explicit intention of the hilya as a substitute for a figurative depiction.[30] [31]

The Ottoman hilye format customarily starts with a basmala, shown on meridian, and is separated in the middle past Quran 21:107:[32] "And Nosotros have not sent you but as a mercy to the worlds".[31] Four compartments set around the cardinal i oft contain the names of the Rightly-Guided Caliphs, Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali, each followed by "radhi Allahu anhu" ("may God be pleased with him").

-

Hilye by Hâfiz Osman

-

Hilye by Hâfiz Osman

-

Hilye by Hâfiz Osman

-

Hilye past Mehmed Tahir Efendi (d. 1848)

-

Hilye by Kazasker Mustafa İzzet Efendi (1801–1876)

-

Hilye by Kazasker Mustafa İzzet Efendi

-

Hilye inscribed on the petals of a pinkish rose symbolising Muhammad (18th century).

Calligraphic representations

The most common visual representation of the Muhammad in Islamic art, especially in Arabic-speaking areas, is by a calligraphic representation of his proper name, a sort of monogram in roughly circular course, often given a decorated frame. Such inscriptions are normally in Arabic, and may rearrange or echo forms, or add a blessing or honorific, or for example the discussion "messenger" or a contraction of information technology. The range of means of representing Muhammad'due south proper name is considerable, including ambigrams; he is also oft symbolised by a rose.

The more than elaborate versions relate to other Islamic traditions of special forms of calligraphy such every bit those writing the names of God, and the secular tughra or elaborate monogram of Ottoman rulers.

-

Muhammad'south proper name in Thuluth, an Arabic calligraphic script; the smaller writing in the top left means "Peace exist upon him"

-

Calligraphic representation of Muhammad'south name, painted on the wall of a mosque in Edirne in Turkey

-

Calligraphy tile from Turkey (18th century), containing the names of God, Muhammad, and his first four successors, Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Ali

-

Late 18th- or early on 19th-century calligraphic panel past Mustafa Rakim

-

Mirror calligraphy of Muhammad's name

-

Decoupage calligraphy (18th or 19th century) with Muhammad's name in mirror script, top middle; the area beneath represents a mihrab, or prayer niche

-

Palestinian pottery calligraphy featuring the names of God (الله) and Muhammad (محمد)

-

Ambigram – Muhammad (محمد) upside downward is read as Ali (علي), and vice versa

-

Tile from a 14th-century mausoleum in Uzbekistan, inscribed with Muhammad'due south name (محمد) in square Kufic; one of a set used to frame a doorway

-

Mosque cupola, with Quranic inscriptions and Kufic representations of Allah's and Muhammad's names worked into the tiling

-

Banna'i on the Royal Mosque in Isfahan, Iran, with square Kufic repeats of Muhammad's and Ali'south names

Figurative visual depictions

Throughout Islamic history, depictions of Muhammad in Islamic fine art were rare.[13] Notwithstanding, there exists a "notable corpus of images of Muhammad produced, by and large in the course of manuscript illustrations, in various regions of the Islamic world from the thirteenth century through modernistic times".[33] Depictions of Muhammad date back to the get-go of the tradition of Persian miniatures as illustrations in books. The illustrated volume from the Persianate globe (Warka and Gulshah, Topkapi Palace Library H. 841, attributed to Konya 1200–1250) contains the 2 earliest known Islamic depictions of Muhammad.[34]

This book dates to before or just around the time of the Mongol invasion of Anatolia in the 1240s, and before the campaigns against Persia and Republic of iraq of the 1250s, which destroyed bully numbers of books in libraries. Recent scholarship has noted that, although surviving early examples are now uncommon, generally human figurative art was a continuous tradition in Islamic lands (such as in literature, scientific discipline, and history); as early on as the 8th century, such art flourished during the Abbasid Caliphate (c. 749 - 1258, across Spain, North Africa, Egypt, Syria, Turkey, Mesopotamia, and Persia).[35]

Christiane Gruber traces a evolution from "veristic" images showing the whole body and face, in the 13th to 15th centuries, to more "abstract" representations in the 16th to 19th centuries, the latter including the representation of Muhammad past a special type of calligraphic representation, with the older types as well remaining in utilize.[36] An intermediate type, outset found from about 1400, is the "inscribed portrait" where the face of Muhammad is blank, with "Ya Muhammad" ("O Muhammad") or a similar phrase written in the space instead; these may be related to Sufi idea. In some cases the inscription appears to have been an underpainting that would subsequently be covered by a face or veil, then a pious deed by the painter, for his eyes lonely, but in others information technology was intended to be seen.[33] Co-ordinate to Gruber, a good number of these paintings afterward underwent iconoclastic mutilations, in which the facial features of Muhammad were scratched or smeared, as Muslim views on the acceptability of veristic images inverse.[37]

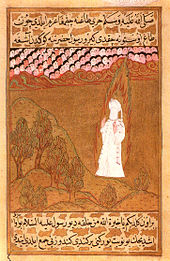

A number of extant Western farsi manuscripts representing Muhammad engagement from the Ilkhanid period under the new Mongol rulers, including a Marzubannama dating to 1299. The Ilkhanid MS Arab 161 of 1307/8 contains 25 illustrations found in an illustrated version of Al-Biruni's The Remaining Signs of By Centuries, of which v include depictions Muhammad, including the two last images, the largest and most accomplished in the manuscript, which emphasize the relation of Muhammad and `Ali co-ordinate to Shi`ite doctrine.[38] According to Christiane Gruber, other works utilise images to promote Sunni Islam, such equally a set up of Mi'raj illustrations (MS H 2154) in the early 14th century,[39] although other historians have dated the same illustrations to the Jalayrid catamenia of Shia rulers.[40]

Muhammad, shown with a veiled face up and halo, at Mountain Hira (16th-century Ottoman illustration of the Siyer-i Nebi)

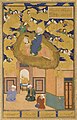

Depictions of Muhammad are also found in Persian manuscripts in the following Timurid and Safavid dynasties, and Turkish Ottoman art in the 14th to 17th centuries, and beyond. Perhaps the about elaborate cycle of illustrations of Muhammad'southward life is the copy, completed in 1595, of the 14th-century biography Siyer-i Nebi commissioned past the Ottoman sultan Murat Three for his son, the future Mehmed III, containing over 800 illustrations.[41]

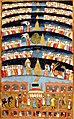

Probably the commonest narrative scene represented is the Mi'raj; co-ordinate to Gruber, "There exist endless single-page paintings of the meʿrāj included in the ancestry of Persian and Turkish romances and epic stories produced from the beginning of the 15th century to the 20th century".[42] These images were also used in celebrations of the ceremony of the Mi'raj on 27 Rajab, when the accounts were recited aloud to male groups: "Didactic and engaging, oral stories of the ascension seem to have had the religious goal of inducing attitudes of praise among their audiences". Such practices are nearly easily documented in the 18th and 19th centuries, but manuscripts from much earlier announced to accept fulfilled the same function.[43] Otherwise a big number of dissimilar scenes may be represented at times, from Muhammad'southward birth to the stop of his life, and his existence in Paradise.[44]

Halo

In the earliest depictions Muhammad may exist shown with or without a halo, the primeval halos beingness round in the style of Christian art,[45] but before long a flaming halo or aureole in the Buddhist or Chinese tradition becomes more common than the circular class found in the West, when a halo is used. A halo or flame may environment but his head, but frequently his whole body, and in some images the body itself cannot be seen for the halo. This "luminous" form of representation avoided the bug caused by "veristic" images, and could be taken to convey qualities of Muhammad'south person described in texts.[46] If the body is visible, the confront may be covered with a veil (see gallery for examples of both types). This form of representation, which began at the start of the Safavid period in Persia,[47] was done out of reverence and respect.[13] Other prophets of Islam, and Muhammad's wives and relations, may be treated in similar ways if they also appear.

T. Due west. Arnold (1864–1930), an early on historian of Islamic art, stated that "Islam has never welcomed painting as a handmaid of faith as both Buddhism and Christianity take done. Mosques take never been busy with religious pictures, nor has a pictorial art been employed for the instruction of the infidel or for the edification of the faithful."[13] Comparison Islam to Christianity, he too writes: "Accordingly, there has never been any historical tradition in the religious painting of Islam – no artistic evolution in the representation of accepted types – no schools of painters of religious subjects; to the lowest degree of all has at that place been any guidance on the part of leaders of religious thought corresponding to that of ecclesiastical authorities in the Christian Church."[13]

Images of Muhammad remain controversial to the present mean solar day, and are non considered acceptable in many countries in the Middle E. For example, in 1963 an account by a Turkish writer of a Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca was banned in Islamic republic of pakistan because it contained reproductions of miniatures showing Muhammad unveiled.[48]

-

"Muhammad at the Ka'ba" from the Siyer-i Nebi (1595).[49] Muhammad is shown with veiled face.

-

Journeying of the Prophet Muhammad in the Majmac al-tawarikh (Compendium of Histories), c. 1425; Timurid. Herat, Afghanistan.

-

Miraj paradigm from 1539 to 1543, reflecting the new, Safavid convention of depicting Muhammad veiled.

-

-

Muhammad and his married woman Aisha freeing the girl of a tribal chief. From the Siyer-i Nebi.

-

Muhammad'south ascent into the Heavens, a journey known as the Mi'raj, as depicted in a copy of the Bostan of Saadi.

-

"Mohammed's Paradise", Persian miniature from The History of Mohammed, BnF, Paris.

Contemporary Islamic republic of iran

Despite the avoidance of the representation of Muhammad in Sunni Islam, images of Muhammed are non uncommon in Iran. The Iranian Shi'ism seems more tolerant on this point than Sunnite orthodoxy.[50] In Iran, depictions accept considerable acceptance to the nowadays 24-hour interval, and may be constitute in the modernistic forms of the poster and postcard.[12] [51]

Since the tardily 1990s, experts in Islamic iconography discovered images, printed on paper in Iran, portraying Mohammed as a teenager wearing a turban.[50] There are several variants, all bear witness the aforementioned juvenile face, identified by an inscription such every bit "Muhammad, the Messenger of God", or a more detailed legend referring to an episode in the life of Muhammad and the supposed origin of the image.[50] Some Iranian versions of these posters attributed the original depiction to a Bahira, a Christian monk who met the immature Muhammad in Syria. By crediting the prototype to a Christian and predating it to the time earlier Muhammad became a prophet, the manufacturers of the image exonerate themselves from whatever wrongdoing.[52]

The motif was taken from a photograph of a young Tunisian taken by the Germans Rudolf Franz Lehnert and Ernst Heinrich Landrock in 1905 or 1906, which had been printed in high editions on motion-picture show post cards till 1921.[50] This depiction has been pop in Iran as a form of curiosity.[52]

In Tehran, a mural depicting the prophet – his face veiled – riding Buraq was installed at a public road intersection in 2008, the just mural of its kind in a Muslim-majority country.[12]

Movie house

Very few films have been made about Muhammad. The 1976 moving picture The Message, also known as Mohammad, Messenger of God, focused on other persons and never directly showed Muhammad or virtually members of his family. A devotional cartoon called Muhammad: The Last Prophet was released in 2004.[53] An Iranian film directed by Majid Majidi was released in 2015 named Muhammad. It is the first part of the trilogy film series on Muhammad past Majid Majidi.

While Sunni Muslims have ever explicitly prohibited the depiction of Muhammad on motion-picture show,[54] contemporary Shi'a scholars accept taken a more than relaxed attitude, stating that it is permissible to depict Muhammad, fifty-fifty in television or movies, if done with respect.[55]

Depiction past non-Muslims

Western representations of Muhammad were very rare until the explosion of images following the invention of the printing press; he is shown in a few medieval images, usually in an unflattering style, often influenced by his brief mention in Dante'due south Divine One-act. Muhammad sometimes figures in Western depictions of groups of influential people in world history. Such depictions tend to exist favourable or neutral in intent; i case can be found at the United states of america Supreme Courtroom building in Washington, D.C. Created in 1935, the frieze includes major historical lawgivers, and places Muhammad aslope Hammurabi, Moses, Confucius, and others. In 1997, a controversy erupted surrounding the frieze, and tourist materials have since been edited to draw the depiction as "a well-intentioned endeavor by the sculptor to honor Muhammad" that "bears no resemblance to Muhammad."[56]

In 1955, a statue of Muhammad was removed from a courthouse in New York Urban center after the ambassadors of Republic of indonesia, Islamic republic of pakistan, and Egypt requested its removal.[57] The extremely rare representations of Muhammad in awe-inspiring sculpture are particularly likely to be offensive to Muslims, as the statue is the classic class for idols, and a fear of any hint of idolatry is the basis of Islamic prohibitions. Islamic art has almost ever avoided big sculptures of any subject, peculiarly gratis-continuing ones; only a few animals are known, mostly fountain-heads, like those in the Lion Courtroom of the Alhambra; the Pisa Griffin is mayhap the largest.

In 1997, the Quango on American–Islamic Relations, a Muslim advocacy grouping in the United States, wrote to United States Supreme Court Primary Justice William Rehnquist requesting that the sculpted representation of Muhammad on the due north frieze inside the Supreme Court building be removed or sanded down. The courtroom rejected CAIR'due south request.[58]

There take too been numerous book illustrations showing Muhammad.

Dante, in The Divine One-act: Inferno, placed Muhammad in Hell, with his entrails hanging out (Canto 28):

- No butt, not even ane where the hoops and staves go every which manner, was e'er divide open up similar one frayed Sinner I saw, ripped from chin to where we fart beneath.

- His guts hung between his legs and displayed His vital organs, including that wretched sack Which converts to shit any gets conveyed downwards the gullet.

- As I stared at him he looked dorsum And with his hands pulled his chest open, Saying, "See how I split open up the cleft in myself! Come across how twisted and broken Mohammed is! Before me walks Ali, his face Cleft from chin to crown, grief–stricken." [59]

This scene was sometimes shown in illustrations of the Divina Commedia earlier modernistic times. Muhammad is represented in a 15th-century fresco Concluding Judgement by Giovanni da Modena and cartoon on Dante, in the Church of San Petronio, Bologna, Italy.[60] and artwork by Salvador Dalí, Auguste Rodin, William Blake, and Gustave Doré.[61]

-

Muhammad, seated on the left, possibly reading from the Quran, equally depicted in the Nuremberg Chronicle [62]

-

Early Renaissance fresco illustrating Dante's Inferno. Muhammad is depicted being dragged downwardly to Hell.

-

-

Portrait of Muhammad every bit a generic "Easterner", from the PANSEBEIA, or A View of all Religions in the World past Alexander Ross (1683).

-

Illustration from La vie de Mahomet, by M. Prideaux, published in 1699. It shows Muhammad holding a sword and a crescent while trampling on a globe, a cross, and the Ten Commandments.

Controversies in the 21st century

The start of the 21st century has been marked past controversies over depictions of Muhammad, non only for recent caricatures or cartoons, but besides regarding the display of historical artwork.

Die Berufung Mohammeds durch den Engel Gabriel by Theodor Hosemann, 1847, published by Spiegel in 1999

In a story on morals at the end of the millennium in December 1999, the High german news magazine Der Spiegel printed on the same folio pictures of "moral apostles" Muhammad, Jesus, Confucius, and Immanuel Kant. In the subsequent weeks, the magazine received protests, petitions and threats against publishing the moving picture of Muhammad. The Turkish TV-station Show TV circulate the phone number of an editor who then received daily calls.[63]

Nadeem Elyas, leader of the Central Quango of Muslims in Germany said that the moving-picture show should not be printed once again in order to avoid hurting the feelings of Muslims intentionally. Elyas recommended to whiten the confront of Muhammad instead.[64]

In June 2001, the Spiegel with consideration of Islamic laws published a picture of Muhammed with a whitened face on its title page.[65] The aforementioned film of Muhammad by Hosemann had been published past the magazine once before in 1998 in a special edition on Islam, but then without evoking similar protests.[66]

In 2002, Italian police reported that they had disrupted a terrorist plot to destroy a church in Bologna, which contains a 15th-century fresco depicting an image of Muhammad (meet higher up).[60] [67]

Examples of depictions of Muhammad existence altered include a 1940 mural at the University of Utah having the name of Muhammad removed from below the painting in 2000 at the request of Muslim students.[68]

Cartoons

In 1990, a Muhammad caricature was published in Indonesian magazine, Senang; it was followed by dissolution of the magazine.[69] In 2005, Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten published a gear up of editorial cartoons, many of which depicted Muhammad. In late 2005 and early 2006, Danish Muslim organizations ignited a controversy through public protests and by spreading knowledge of the publication of the cartoons.[24] According to John Woods, Islamic history professor at the University of Chicago, it was not simply the depiction of Muhammad that was offensive, only the implication that Muhammad was somehow a supporter of terrorism.[18] In Sweden, an online caricature competition was announced in support of Jyllands-Posten, but Foreign Affairs Minister Laila Freivalds and the Swedish Security Service pressured the internet access provider to close the folio downwardly. In 2006, when her involvement was revealed to the public, she had to resign.[lxx] On 12 February 2008 the Danish law arrested 3 men alleged to be involved in a plot to assassinate Kurt Westergaard, 1 of the cartoonists.[71]

Muhammad appeared in the 2001 South Park episode "Super Best Friends". The image was later removed from the 2006 episode "Drawing Wars" and the 2010 episodes "200" and "201" due to controversies regarding Muhammad cartoons in European newspapers.

In 2006, the controversial American animated television comedy program South Park, which had previously depicted Muhammad as a superhero grapheme in the July 4, 2001 episode "Super Best Friends"[72] and has depicted Muhammad in the opening sequence since that episode,[73] attempted to satirize the Danish paper incident. In the episode, "Drawing Wars Office II", they intended to show Muhammad handing a salmon helmet to Peter Griffin, a grapheme from the Fox animated serial Family Guy. Notwithstanding, Comedy Central, who airs South Park, rejected the scene, citing concerns of vehement protests in the Islamic world. The creators of South Park reacted by instead satirizing Comedy Key's double standard for broadcast acceptability by including a segment of "Cartoon Wars Part II" in which American president George W. Bush-league and Jesus defecate on the flag of the United States.

The Lars Vilks Muhammad drawings controversy began in July 2007 with a series of drawings by Swedish artist Lars Vilks which depicted Muhammad equally a roundabout domestic dog. Several art galleries in Sweden declined to evidence the drawings, citing security concerns and fear of violence. The controversy gained international attention after the Örebro-based regional newspaper Nerikes Allehanda published one of the drawings on August 18 to illustrate an editorial on cocky-censorship and freedom of organized religion.[74]

While several other leading Swedish newspapers had published the drawings already, this particular publication led to protests from Muslims in Sweden as well as official condemnations from several foreign governments including Iran,[75] Pakistan,[76] Afghanistan,[77] Egypt[78] and Jordan,[79] also every bit past the inter-governmental Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC).[fourscore] The controversy occurred almost one and a one-half years later on the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy in Kingdom of denmark in early on 2006.

Another controversy emerged in September 2007 when Bangladeshi cartoonist Arifur Rahman was detained on suspicion of showing disrespect to Muhammad. The acting regime confiscated copies of the Bengali-language Prothom Alo in which the drawings appeared. The cartoon consisted of a boy holding a cat conversing with an elderly man. The man asks the boy his name, and he replies "Babu". The older man chides him for not mentioning the name of Muhammad before his proper noun. He then points to the cat and asks the boy what it is called, and the boy replies "Muhammad the true cat".

The cartoon caused a firestorm in People's republic of bangladesh, with militant Islamists enervating that Rahman be executed for blasphemy. A grouping of people torched copies of the paper and several Islamic groups protested, saying the drawings ridiculed Mohammad and his companions. They demanded "exemplary punishment" for the paper'due south editor and the cartoonist. Bangladesh does not have a blasphemy constabulary, although ane had been demanded past the aforementioned extremist Islamic groups.

Charlie Hebdo

three November 2011 comprehend of Charlie Hebdo, renamed Charia Hebdo (Sharia Hebdo). The word airship reads "100 lashes if you don't dice of laughter!"

Comprehend of fourteen January 2015 in the same style as the iii November 2011 cover, with the phrase Je Suis Charlie and the title "All is forgiven."[81]

On ii Nov 2010, the role of the French satirical weekly newspaper Charlie Hebdo at Paris was attacked with a firebomb and its website hacked, after it had announced plans to publish a special edition with Muhammad as its "main editor", and the championship folio with a cartoon of Muhammad had been pre-issued on social media.

In September 2012, the newspaper published a series of satirical cartoons of Muhammad, some of which feature nude caricatures of him. In January 2013, Charlie Hebdo announced that they would make a comic book on the life of Muhammad.[82] In March 2013, Al-Qaeda'due south branch in Yemen, normally known as Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), released a striking list in an edition of their English language-language magazine Inspire. The list included Stéphane Charbonnier, Lars Vilks, three Jyllands-Posten employees involved in the Muhammad cartoon controversy, Molly Norris from the Everybody Draw Mohammed Day and others whom AQAP accused of insulting Islam.[83]

On 7 Jan 2015, the office was attacked over again with 12 shot dead, including Stéphane Charbonnier, and 11 injured.

On 16 October 2020, center-schoolhouse teacher Samuel Paty was killed and beheaded after showing Charlie Hebdo cartoons depicting Muhammad during a class on freedom of spoken communication.

Wikipedia article

In 2008, effectually 180,000 people, many Muslims, signed a petition protesting against the inclusion of Muhammad's depictions in the English Wikipedia's Muhammad commodity.[84] [85] [86]

The petition was opposed to a depiction of Muhammad prohibiting Nasīʾ

The petition opposed a reproduction of a 17th-century Ottoman copy of a 14th-century Ilkhanate manuscript image (MS Arabe 1489) depicting Muhammad as he prohibited Nasīʾ.[87] Jeremy Henzell-Thomas of The American Muslim deplored the petition as one of "these mechanical genu-jerk reactions [which] are gifts to those who seek every opportunity to decry Islam and ridicule Muslims and can only exacerbate a situation in which Muslims and the Western media seem to be locked in an ever-descending screw of ignorance and common loathing."[88]

Wikipedia considered but rejected a compromise that would allow visitors to cull whether to view the folio with images.[86] The Wikipedia community has not acted upon the petition.[84] The site's answers to oft asked questions virtually these images state that Wikipedia does not conscience itself for the benefit of any i grouping.[89]

Metropolitan Museum of Fine art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in January 2010 confirmed to the New York Postal service that it had quietly removed all historic paintings which contained depictions of Muhammad from public exhibition. The Museum quoted objections on the part of conservative Muslims which were "under review." The museum's activeness was criticized equally excessive political definiteness, as were other decisions taken close to the aforementioned time, including the renaming of the "Primitive Fine art Galleries" to the "Arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas" and the projected "Islamic Galleries" to "Arab Lands, Turkey, Islamic republic of iran, Central Asia and After South Asia".[90]

Everybody Draw Mohammed Day

Everybody Describe Mohammed 24-hour interval was a protestation against those who threatened violence against artists who drew representations of Muhammad. Information technology began equally a protest against the action of One-act Primal in forbidding the circulate of the Southward Park episode "201" in response to death threats against some of those responsible for the segment. Observance of the day began with a drawing posted on the Internet on Apr 20, 2010, accompanied by text suggesting that "everybody" create a cartoon representing Muhammad, on May 20, 2010, as a protest against efforts to limit freedom of voice communication.

Muhammad Art Exhibit & Contest

A May 3, 2015, event held in Garland, Texas, held past American activists Pamela Geller and Robert Spencer, was the scene of a shooting past two individuals who were later themselves shot and killed outside the issue.[91] Police officers profitable in security at the event returned burn down and killed the two gunmen. The event offered a $10,000 prize and was said to be in response to the January 2015 attacks on the French mag Charlie Hebdo. One of the gunmen was identified as a former terror doubtable, known to the Federal Bureau of Investigation.[92]

Batley Grammer School

In March 2021 a teacher at Batley Grammar School in England was suspended, and the headmaster issued an amends, after the teacher showed one or more than of the Charlie Hebdo cartoons to pupils during a lesson. The incident sparked protests outside the school, demanding the resignation or sacking of the instructor involved.[93] Commenting on the situation, the UK government's Communities Secretary, Robert Jenrick, said teachers should be able to "accordingly testify images of the prophet" in class and the protests are "deeply unsettling" due to the UK being a "gratis gild". He added teachers should "not be threatened" by religious extremists.[94]

See also

- Qadam Rasul

- The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie

- 2006 Idomeneo controversy

General:

- Censorship in Islamic societies

- Criticism of Muhammad

Notes

- ^ a b T. W. Arnold (June 1919). "An Indian Picture of Muhammad and His Companions". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 34, No. 195. 34 (195): 249–252. JSTOR 860736.

- ^ Jonathan Bloom & Sheila Blair (1997). Islamic Arts . London: Phaidon. p. 202.

- ^ The Koran Does Non Forbid Images of the Prophet, 9 January 2015, Christiane Gruber, Academy of Michigan]

- ^ Professor Christiane Gruber Across Conventionalities

- ^ What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam, John L. Esposito - 2011 p. 14; for hadith see Sahih al-Bukhari, Hadith: 7.834, 7.838, vii.840, vii.844, 7.846.

- ^ Gruber (2010), p. 27.

- ^ Cosman, Pelner and Jones, Linda Gale. Handbook to life in the medieval world, p. 623, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 0-8160-4887-8, ISBN 978-0-8160-4887-8

- ^ Gruber (2010), p.27 (quote) and 43.

- ^ Gruber (2005), pp. 239, 247–253.

- ^ Brendan Jan (1 February 2009). The Arab Conquests of the Center Eastward . Twenty-First Century Books. p. 34. ISBN978-0-8225-8744-6 . Retrieved 14 Nov 2011.

- ^ Omid Safi (2 November 2010). Memories of Muhammad: Why the Prophet Matters. HarperCollins. p. 171. ISBN978-0-06-123135-3 . Retrieved xiv November 2011.

- ^ a b c Christiane Gruber: Images of the Prophet In and Out of Modernity: The Curious Case of a 2008 Mural in Tehran, in Christiane Gruber; Sune Haugbolle (17 July 2013). Visual Civilisation in the Mod Eye East: Rhetoric of the Image. Indiana University Press. pp. 3–31. ISBN978-0-253-00894-7. See besides [1] and [ii].

- ^ a b c d e Arnold, Thomas W. (2002–2011) [First published in 1928]. Painting in Islam, a Study of the Place of Pictorial Fine art in Muslim Culture. Gorgias Press LLC. pp. 91–9. ISBN978-1-931956-91-8.

- ^ a b Dirk van der Plas (1987). Effigies dei: essays on the history of religions. BRILL. p. 124. ISBN978-xc-04-08655-5 . Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ a b Ernst, Carl W. (August 2004). Post-obit Muhammad: Rethinking Islam in the Contemporary World. UNC Printing Books. pp. 78–79. ISBN978-0-8078-5577-5 . Retrieved fourteen Nov 2011.

- ^ Devotion in pictures: Muslim popular iconography – Introduction to the exhibition, University of Bergen.

- ^ Office of the Curator (2003-05-08). "Court Friezes: N and South Walls" (PDF). Information Sheet, Supreme Court of the United States . Retrieved 2007-07-08 .

- ^ a b "Explaining the outrage". Chicago Tribune. 2006-02-08.

- ^ a b Devotion in pictures: Muslim popular iconography – The prophet Muhammad, University of Bergen

- ^ Eaton, Charles Le Gai (1985). Islam and the destiny of man. State Academy of New York Printing. p. 207. ISBN978-0-88706-161-v.

- ^ Thomas Walker Arnold says "It was not merely Sunni schools of law but Shia jurists also who fulminated against this figured art. Because the Persians are Shiites, many Europeans writers have causeless that the Shia sect had non the same objection to representing living being every bit the rival set of the Sunni; but such an opinion ignores the fact that Shiisum did not become the country church in Persia until the rise of the Safivid dynasty at the kickoff of the 16th century."

- ^ "Islamic Figurative Art and Depictions of Muhammad". religionfacts.com. Retrieved 2007-07-06 .

- ^ a b Richard Halicks (2006-02-12). "Images of Muhammad: Three ways to run into a cartoon". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- ^ a b c Grabar, Oleg (2003). "The Story of Portraits of the Prophet Muhammad". Studia Islamica (96): 19–38. doi:10.2307/1596240. JSTOR 1596240.

- ^ Asani, Ali (1995). Celebrating Muhammad: Images of the Prophet in Pop Muslim Piety. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. pp. 64–65.

- ^ Leslie, Donald (1986). Islam in Traditional China. Canberra: Canberra Higher of Advanced Instruction. p. 73.

- ^ Ibn Sa'd – Kitabh al-Tabaqat al-Kabir, as translated by S. Moinul and H.K. Ghazanfar, Kitab Bhavan, New Delhi, n.d.

- ^ Gruber (2005), p.231-232

- ^ F. E. Peters (10 November 2010). Jesus and Muhammad: Parallel Tracks, Parallel Lives. Oxford University Press. pp. 160–161. ISBN978-0-xix-974746-7 . Retrieved five November 2011.

- ^ a b Jonathan E. Brockopp (xxx April 2010). The Cambridge companion to Muḥammad. Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN978-0-521-71372-6 . Retrieved six November 2011.

- ^ Quran 21:107

- ^ a b Gruber (2005), p. 240-241

- ^ Grabar, p. 19; Gruber (2005), p. 235 (from where the appointment range), Blair, Sheila S., The Development of the Illustrated Book in Islamic republic of iran, Muqarnas, Vol. 10, Essays in Honor of Oleg Grabar (1993), p. 266, BRILL, JSTOR says "c. 1250"

- ^ J. Bloom & S. Blair (2009). Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc. pp. 192 and 207. ISBN978-0-xix-530991-1.

- ^ Gruber (2005), 229, and throughout

- ^ Gruber (2005), 229

- ^ Gruber (2010), pp.27-28

- ^ Gruber (2010), quote p. 43; generally pp.29-45

- ^ Gruber, Christiane (2010-03-xv). The Ilkhanid Book of Ascension . Tauris Academic Studies. p. 25. ISBN978-1-84511-499-2.

- ^ Tanındı, Zeren (1984). Siyer-i nebî: İslam tasvir sanatında Hz. Muhammedʹin hayatı. Hürriyet Vakfı Yayınları.

- ^ Gruber (Iranica)

- ^ Gruber (2010), p.43

- ^ The nascence is rare, merely appears in an early manuscript in Edinburgh

- ^ Arnold, 95

- ^ Gruber, 230, 236

- ^ Brend, Barbara. Islamic Fine art, p. 161, British Museum Press.

- ^ Schimmel, Annemarie, Deciphering the signs of God: a phenomenological arroyo to Islam, p.45, n. 86, SUNY Press, 1994, ISBN 0-7914-1982-7, ISBN 978-0-7914-1982-3

- ^ "Ottomans : religious painting". Retrieved one May 2016.

- ^ a b c d Pierre Centlivres, Micheline Centlivres-Demont: Une étrange rencontre. La photographie orientaliste de Lehnert et Landrock et l'image iranienne du prophète Mahomet, Études photographiques Nr. 17, Nov 2005 (in French)

- ^ Gruber (2010), p.253, illustrates a postcard bought in 2001.

- ^ a b "Mohammed | Iconic Photos". Iconicphotos.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2013-06-06 .

- ^ "Fine Media Group". Archived from the original on 2006-05-09. Retrieved 2006-03-11 .

- ^ Alessandra. Raengo & Robert Stam (2004). A Companion To Literature And Film . Blackwell Publishing. p. 31. ISBN0-631-23053-X.

- ^ "Istifta". Archived from the original on 2006-10-17. Retrieved 2006-03-10 .

- ^ Biskupic, Joan (March 11, 1998). "Lawgivers: From Two Friezes, Great Figures Of Legal History Gaze Upon The Supreme Court Bench". The Washington Post . Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ "Archive "Montreal News Network": Images of Muhammad, Gone for Good". 2006-02-12. Archived from the original on 2013-02-x. Retrieved 2006-03-10 .

- ^ MSN : "How the "Ban" on Images of Muhammad Came to Be" by Jackie Bischof Archived May 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine January 19, 2015.

- ^ Seth Zimmerman (2003). The Inferno of Dante Alighieri. iUniverse. p. 191. ISBN0-595-28090-0.

- ^ a b Philip Willan (2002-06-24). "Al-Qaida plot to blow upwards Bologna church fresco". The Guardian.

- ^ Ayesha Akram (2006-02-11). "What's backside Muslim cartoon outrage". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Smith, Charlotte Colding (2015). Images of Islam, 1453–1600: Turks in Federal republic of germany and Key Europe. Routledge. p. 26. ISBN9781317319634.

- ^ Terror am Telefon, Spiegel, February 7, 2000

- ^ Carolin Emcke: Fanatiker sind leicht verführbar, Interview with Nadeem Elyas, February seven, 2000

- ^ 6. Februar 2006 Betr.: Titel, Spiegel, half dozen February 6, 2006

- ^ Spiegel Special i, 1998, page 76

- ^ "Italian republic frees Fresco Suspects". The New York Times. 2002-08-22.

- ^ "Muhammad depiction controversy lurks in U's past". Daily Utah Chronicle. University of Utah. 22 February 2006. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved xvi November 2017.

- ^ Tempomedia (1990-11-10). "Wajah rasulullah di tengah umat". Tempo . Retrieved 2020-05-05 .

- ^ "Swedish foreign minister resigns over cartoons". Reuters AlertNet. Archived from the original on 22 March 2006. Retrieved 2006-03-21 .

- ^ Staff. Danish cartoons 'plotters' held BBC, 12 February 2008

- ^ "Super Best Friends". South Park. Season 5. Episode 68. 2001-07-04.

- ^ "Ryan j Budke. "South Park's been showing Muhammad all season!" TVSquad.com; April 15, 2006". Tvsquad.com. Retrieved 2013-06-06 .

- ^ Ströman, Lars (2007-08-18). "Rätten att förlöjliga en religion" (in Swedish). Nerikes Allehanda. Archived from the original on 2007-09-06. Retrieved 2007-08-31 .

English translation: Ströman, Lars (2007-08-28). "The correct to ridicule a religion". Nerikes Allehanda. Archived from the original on 2007-08-30. Retrieved 2007-08-31 . - ^ "Islamic republic of iran protests over Swedish Muhammad drawing". Agence France-Presse. 2007-08-27. Archived from the original on 2007-08-29. Retrieved 2007-08-27 .

- ^ "Islamic republic of pakistan CONDEMNS THE PUBLICATION OF OFFENSIVE SKETCH IN SWEDEN" (Printing release). Pakistan Ministry of Strange Affairs. 2007-08-30. Archived from the original on 2007-09-04. Retrieved 2007-08-31 .

- ^ Salahuddin, Sayed (2007-09-01). "Indignant Afghanistan slams Prophet Mohammad sketch". Reuters . Retrieved 2007-09-09 .

- ^ Fouché, Gwladys (2007-09-03). "Egypt wades into Swedish cartoons row". The Guardian . Retrieved 2007-09-09 .

- ^ "Jordan condemns new Swedish Mohammed cartoon". Agence France-Presse. 2007-09-03. Retrieved 2007-09-09 . [ dead link ]

- ^ "The Secretarial assistant General strongly condemned the publishing of cursing caricatures of prophet Muhammad by Swedish creative person" (Press release). Organisation of the Islamic Conference. 2007-08-30. Archived from the original on 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2007-09-09 .

- ^ "How I created the Charlie Hebdo magazine cover: cartoonist Luz'south statement in full". The Telegraph. 13 Jan 2015. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015.

- ^ Taylor, Jerome (two Jan 2013). "Information technology'due south Charlie Hebdo's right to draw Muhammad, just they missed the opportunity to do something profound". The Contained . Retrieved 12 Oct 2014.

- ^ "Has al-Qaeda Struck Back? Office 1". 8 January 2015. Retrieved thirteen January 2017.

- ^ a b "Wikipedia defies 180,000 demands to remove images of the Prophet". The Guardian. 17 February 2008.

- ^ "Muslims Protest Wikipedia Images of Muhammad". Fox News. 2008-02-06. Archived from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2008-02-07 .

- ^ a b Noam Cohen (2008-02-05). "Wikipedia Islam Entry Is Criticized". The New York Times . Retrieved 2008-02-07 .

- ^ MS Arabe 1489. The image used by Wikipedia is hosted on Wikimedia Commons (upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0d/Maome.jpg). The reproduction originates from the website of the Bibliothèque nationale de France [iii]

- ^ "Wikipedia and Depictions of the Prophet Muhammad: The Latest Inane Lark". x February 2008.

- ^ "Wikipedia Refuses To Delete Picture Of Muhammad". Information Calendar week. vii Feb 2008. Archived from the original on 2012-09-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ 'Jihad' jitters at Met – Mohammed art gone by Isabel Vincent, 10 Jan 2010.

- ^ Kevin Conlon and Kristina Sgueglia, CNN (4 May 2015). "Two shot dead after they open fire at Mohammed cartoon event in Texas". CNN . Retrieved one May 2016.

- ^ ABC News. "Garland Shooting Suspect Elton Simpson'southward Father Says Son 'Made a Bad Choice'". ABC News . Retrieved one May 2016.

- ^ "Batley Grammar School teacher suspended after Muhammad drawing protest". BBC News. 25 March 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "Batley schoolhouse protests: Prophet Muhammad cartoon row 'hijacked'". BBC News. 26 March 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

References

- Arnold, Thomas W. (2002–2011) [1928]. Painting in Islam, a Study of the Identify of Pictorial Art in Muslim Culture. Gorgias Press LLC. pp. 91–99. ISBN978-i-931956-91-8.

- Ali, Wijdan, M. Kiel; N. Landman; H. Theunissen (eds.), "From the Literal to the Spiritual: The Development of Prophet Muhammad's Portrayal from 13th Century Ilkhanid Miniatures to 17th Century Ottoman Art" (PDF), Proceedings of the 11th International Congress of Turkish Art, The Netherlands: Utrecht, vol. vii, no. ane–24, p. 7, archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-12-03

- Grabar, Oleg, The Story of Portraits of the Prophet Muhammad, in Studia Islamica, 2004, p. 19 onwards.

- "Gruber (2005)", Gruber, Christiane, Representations of the Prophet Muhammad in Islamic painting, in Gulru Necipoglu, Karen Leal eds., Muqarnas, Volume 26, 2009, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-17589-X, 9789004175891, google books

- "Gruber (2010)", Gruber, Christiane J., The Prophet's ascension: cantankerous-cultural encounters with the Islamic mi'rāj tales, Christiane J. Gruber, Frederick Stephen Colby (eds), Indiana University Printing, 2010, ISBN 0-253-35361-0, ISBN 978-0-253-35361-0, google books

- "Gruber (Iranica)", Gruber, Christiane, "MEʿRĀJ ii. Illustrations", in Encyclopedia Iranica, 2009, online

Further reading

- Gruber, Christiane J.; Shalem, Avinoam (eds), The Epitome of the Prophet Between Platonic and Ideology: A Scholarly Investigation, De Gruyter, 2014, ISBN 9783110312386, google books, Introduction

- Gruber, Christiane J., "Images", in: Fitzpatrick, Coeli; Walker, Adam Hani (eds), Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God, ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2014, ISBN 9781610691772, google books

External links

- Devotion in pictures: Muslim popular iconography, University of Bergen

- "Religious" Paintings in Islamic Fine art

- "The Koran Does Not Forbid Images of the Prophet", Newsweek, nine January 2015, by Christiane Gruber,

- Article with additional cartoons: Collection two

- Mohammed Paradigm Archive: Depictions of Mohammed Throughout History

- Muhammad in Dante's Inferno 28

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Depictions_of_Muhammad

0 Response to "Art and Imagery Depicting the Prophet Muhammad Were for the Purpose of"

Enregistrer un commentaire